C-FCN PyTorch Implementation

Early 2020s, I joined a team working on launching high-altitude balloons (HABs) for an aerial remote sensing project. The launch were in rural Victoria, Australia and we built everything from payloads to telemetry.

The mission was simple in theory - send camera, several other sensors, and transmitter to the stratosphere (~20km altitude), collecting visual data and transmit what we could in real-time over a shaky data link. Naturally, almost always, things turned out to be far more complex than that.

My role was to design and deploy the onboard machine learning pipeline, basically making the model work on a sub-$1000 edge device, in the sky, without crashing.

At that altitude, even basic things get weird. Power draw becomes a real problem when cooling becomes troublesome as there's hardly any air to convect heat away plus we have to ensure there it last over 24 hour to retrieve the payload in case it lost in the middle of the dense forest. As the result, we had to keep our payload light, power-efficient, and dead simple.

Furthermore, because bandwidth was extremely limited, we couldn't just stream every frame down, we needed a way to filter out unnecessary frames and only send down those that are useful.

That's where my work started. To build a segmentation system that could run on a Jetson with no fallback.

The Challenge

The problem wasn't just "do la segmentation" but how do you really run a convolutional neural network (CNN) on a shoebox-size payload with barely enough power to charge a phone.

Running inference on-device sounds cool until your CPU throttles, memory is tight, and you have ~2W of power to play with system-wide.

The problem was quite clear: we need a model that was light enough to fit in memory run at a few frames per minute, inference must be fast and stable on constraint, a pipeline that doesn't stall the system.

Off-the-shelf sematic segmentation models were either too big, too slow, or too fragile and traditional algorithm perform under our bar. So I adapted an architecture call C-FCN, reworked to our use case.

Architecture and Implementation

To meet the power and latency constrains of the onbard system, I adapted the C-FCN, trading a bit of it's efficiency for effectiveness. You can read the original paper here.

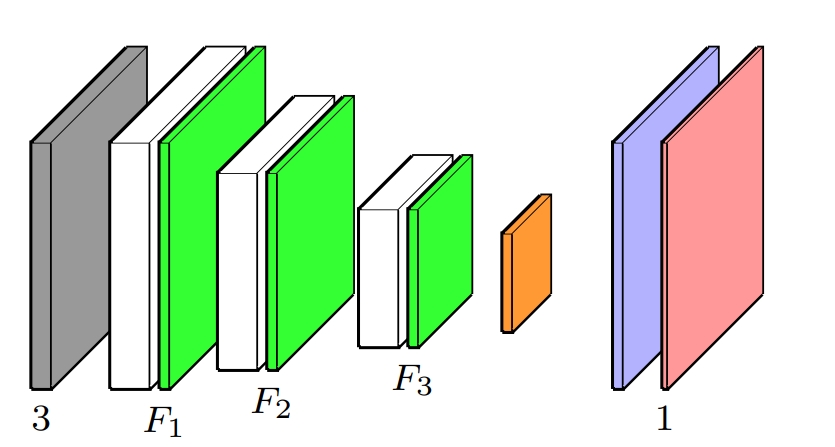

Take a lot of inspiration from the paper, the architecture is:

The encoder uses three layers of depthwise separable convolutions (DSC). Unlike standard convolutions, DSCs break the operation into two lightweight steps: one that handles spatial filtering per channel (depthwise), and another that mixes channels (pointwise).

This significantly reduced both the model size and the number of floating-point operations (FLOPs), while preserving most of the accuracy. In testing, the performance drop was negligible, especially considering the resource savings — ideal for our low-power, onboard compute environment.

The decoder stage consists of three layers of bilinear upsampling, the same as in the original C-FCN architecture. Bilinear interpolation is non-parametric (it learns nothing) and very cheap to run, making it perfect when you need to scale up resolution without paying a performance penalty.

Bilinear upsampling alone tends to produce slightly blurry outputs due to its smoothing nature. To compensate, I added a skip connection from the original input image, concatenating it with the upsampled feature map. This combined tensor is then passed through a final 2D convolution layer.

While I can’t fully quantify why this worked so well, the intuition is simple: the original image contains high-frequency edge and texture information that the model struggles to reconstruct after heavy downsampling and upsampling. Feeding the raw image back in helps preserve those fine details, and empirically, it made a noticeable difference in output clarity.

Performance

- Parameter count: Just 273 parameters — yes, total.

- For comparison: even a small UNet typically has ~10,000+ parameters.

- Runtime: Roughly 10× faster than a baseline small UNet under the same conditions.

- Memory footprint: Roughly equivalent to one image in RAM, thanks to the lightweight architecture and single skip connection.

The model was quantized to FP16 using TensorRT, which helped reduce both inference latency and power consumption. While I didn’t measure exact wattage, we were running the entire Jetson system (model + sensor + telemetry) under ~2W total.

Given the model’s size and simplicity (just a few hundred FLOPs per frame), I’d estimate the ML component drew less than 200–300 mW, which made it viable for 12+ hour flights on battery.

The Launch

We launched three balloons on the day, one of them carrying my payload. The lift-off happened at a remote field site in rural Victoria, right before midday.

It’s still wild to think we had a neural network making decisions in real time, 20 km above the earth, with nothing but sky and silence around it.